By Lyra Fontaine

Researchers like Em Triolo (ME Ph.D. ’24) are testing imaging methods that could provide insights about brain diseases like Alzheimer’s.

As a graduate student and research scientist in Kurtlab, Em Triolo has developed methods of measuring and imaging the mechanical properties of the human brain. The biomechanics of the brain could provide key insights into brain health, says Mehmet Kurt, an ME associate professor and the director of Kurtlab.

To calculate and map the brain’s properties at a high resolution, Triolo uses a technique called magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). This method combines magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with sound waves to measure the stiffness or softness of brain tissue. By doing this, researchers can create detailed images that depict the varying levels of stiffness in different parts of the brain.

“We know the speed of sound changes in different materials, so we apply a sound wave to brain tissue and use MRI to measure the speed of sound as it travels through the brain,” Triolo says. “Based on how fast the wave is moving, we can then calculate the stiffness or softness of that part of the brain.”

A better understanding of these mechanical properties can provide information about different tissue structures, such as cell density and inflammation, that could potentially be used to diagnose disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

“Diseases can cause microstructural changes in tissue, which in turn can change tissues’ mechanical properties,” Kurt says. Tissue stiffness has been used to diagnose fibrosis in the liver, for example. “Brain MREs are useful because different stages of Alzheimer’s disease will have varying levels of brain stiffness based on factors such as plaque, tissue degeneration and atrophy.”

Detailed images of the brain

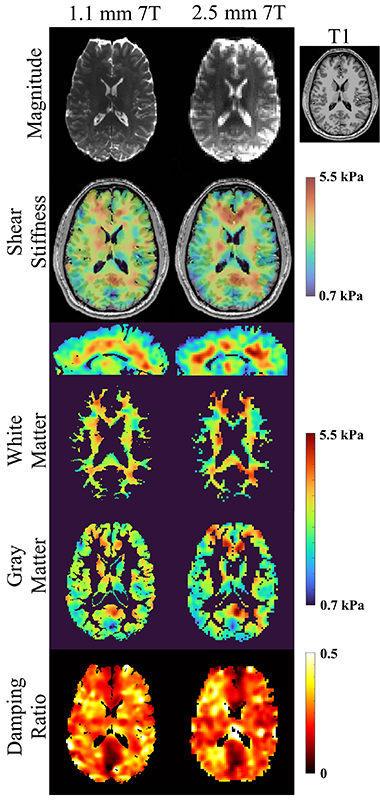

Images of brain scans from a study that used MRI and sound waves at a high field strength to measure brain stiffness and generate detailed medical images. Red represents the stiffer areas of the brain and blue represents the softer parts.

In a recent study, researchers including Triolo and Kurt demonstrated that using MRI and sound waves at a high field strength can reliably measure brain stiffness and generate anatomically detailed medical images. The research, done in collaboration with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, involved brain scans of 18 healthy volunteers using an ultra-high magnetic field strength 7-Tesla (7T) MRI machine at Mount Sinai.

Because of its stronger magnetic field strength, the 7T MRI machine provides higher resolution images compared to the more commonly used 1.5T and 3T machines. Kurt says that this is one of the first large-scale 7T studies in human brains. The research was funded by a $2 million National Science Foundation grant Kurt received in 2020 while he was a faculty member at the Stevens Institute of Technology.

“We wanted to find out if the stiffness measurements are different because 7T has a stronger magnet,” Kurt says. “We found that we can measure the same mechanical properties but with improved resolution.”

The researchers are also using this technique to measure the brain mechanics of people with Alzheimer’s disease. It’s crucial to have reliable, detailed information about certain small regions of the brain to better understand diseases like Alzheimer’s, says Kurt.

“The goal is to detect brain damage at the earliest stage possible,” Triolo says. “As the tissue regenerates and moves through different stages of disease, we’re hoping to detect changes in stiffness so that clinicians can potentially intervene before larger changes like brain shrinkage occur.”

Information about brain stiffness could also help track the progression of brain diseases, assist in surgical planning, and aid in identifying brain tumors. It may also provide insights into aging or pediatric development.

From athlete to brain imaging researcher

Em Triolo at the 2024 UW graduation

Triolo’s interest in engineering started early, while building and tinkering with toys as a child and enjoying math and science classes. While studying biomedical engineering at The College of New Jersey (TCNJ), Triolo took an interest in medical device research, specifically in the field of assistive and diagnostic technology. At TCNJ, they improved the hardware and software design of a five-fingered orthotic exoskeleton hand meant to improve the user’s grip strength.

When applying to master’s degree programs, Triolo was particularly drawn to the neuroimaging work being done in Kurtlab, which was then located at the Stevens Institute of Technology. As a former student athlete in gymnastics, Triolo had experienced concussions that required brain imaging, and hoped to improve outcomes for people with brain disorders.

After Kurtlab relocated to the UW, Triolo moved from the East Coast to the West Coast to continue their research. Despite moving in the midst of a global pandemic, Triolo quickly felt welcomed into the UW community through courses, research activities, faculty support and getting involved in the ME Graduate Student Association (MEGA).

“I believe I have found my lifelong research passion through my projects as a graduate student, and I hope to spend the rest of my career tackling research problems involving brain imaging and diagnosis of disorders involving the brain,” Triolo says.

In winter 2024, Triolo will begin a new role as a staff research scientist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s research imaging center.

“Em is a stellar researcher who has accomplished so much,” Kurt says.

Originally published December 2, 2024